March 31, 2025

My Review of the 2024 60th Venice Biennale!

Click HERE to read my review of Foreigners Everywhere, curated by Adriano Pedrosa, titled: “Outing the Global South: “Foreigners Everywhere,” the 60th Venice Biennale Arte, Pleasantly Cancels Itself Out,” published in Filthy Dreams.

Click HERE to read my review of Foreigners Everywhere, curated by Adriano Pedrosa, titled: “Outing the Global South: “Foreigners Everywhere,” the 60th Venice Biennale Arte, Pleasantly Cancels Itself Out,” published in Filthy Dreams.

Written by Bradley Wester at 3:07 pm

January 26, 2024

PUSHCART PRIZE & NEW AMERICAN ESSAYS Nominations!

Read my nominated essay, “SHINY OBJECT,” published in bioStories, or listen to my professional studio recording of the essay HERE. A powerful coming-of-age story against the terrifying backdrop of Queer murder and arson in my hometown of New Orleans.

Written by Bradley Wester at 5:09 pm

My essay/review: “‘When Is Art’ in the Queer State of Florida?”

Read HERE to discover what the Miami Art Fairs, Ringling Barnum and Bailey Circus, Ron DeSantis, Brazilian artist Hélio Oiticica, and Belgian artist Lieven De Boeck have in common. My second piece for WHITEHOT MAGAZINE OF CONTEMPORARY ART.

Written by Bradley Wester at 4:42 pm

June 8, 2023

My Review of “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” Curated by Lara Pan

I am now a contributing writer for WHITEHOT MAGAZINE OF CONTEMPORARY ART. Read my FIRST REVIEW for the magazine for a show of international artists at the “intersection of art and science” at the Jamestown Arts Center.

Written by Bradley Wester at 5:23 pm

My Review of the Venice Biennale THE MILK OF DREAMS

I had the honor of being invited to the 2022 Venice Biennale Arte Pre-Opening as a writer. It was an extraordinary experience. Click here for my review in Filthy Dreams, the publication’s third most-read article that year.

I had the honor of being invited to the 2022 Venice Biennale Arte Pre-Opening as a writer. It was an extraordinary experience. Click here for my review in Filthy Dreams, the publication’s third most-read article that year.

Written by Bradley Wester at 5:09 pm

August 8, 2021

PUBLISHED WRITING

CHECK OUT MY NEW WRITING HERE. Since July of 2019, I’ve been a member of Medium.com. Several excerpts from my manuscript, Growing Up Under Water, have been curated into publications there, among other articles/essays—from my New Orleans roots to the New York art world.

Written by Bradley Wester at 5:50 pm

SIGNED with LITERARY AGENT!

THRILLED to announce that on August 28th, 2020, I signed with Literary Agent Paula Munier of Talcott Notch Literary for my creative nonfiction manuscript “Growing Up Under Water”

Manuscript’s Logline:

A delicate boy in Southern Gothic, mid-century New Orleans uses his beauty and talent to escape a cruel mother and family history of violence only to deepen his wounds while negotiating the glamorous but treacherous 1980’s New York art-world. After surviving the AIDS crisis, sexual assault, heartbreak, 9/11, Hurricane Katrina, it is his redneck, homophobic, older brother’s threat to shoot him at their mother’s funeral—precipitated by Trump’s ascendency—that finally jeopardizes his lifetime faith in art’s redemption.

Written by Bradley Wester at 5:26 pm

January 20, 2020

My article “The Trouble with Metaphor” published on Medium.com

The Trouble with Metaphor, And the radical autonomy of art. Read it here.

“What are the materials doing? What is your artwork doing?” I’d ask.

Never, “What does your artwork represent?” — to my student’s consternation.

Written by Bradley Wester at 12:45 am

July 28, 2019

FINALIST! for 47th NEW MILLENNIUM WRITING AWARD FOR NONFICTION — July 2019

SHINY OBJECT by Bradley Wester is a FINALIST for the 2019 New Millennium Writing Awards in NONFICTION, Writing Contest XLVII. (Click HERE for winner and other finalists.)

SHINY OBJECT is a story of first love, heartbreak, and the 1973 Upstairs Lounge arson in New Orleans, my hometown. It was the deadliest attack on homosexuals in U.S. history (until the more recent Orlando PULSE massacre) and it took place on Bradley’s 18th birthday. SHINY OBJECT is a stand-alone chapter in Growing Up Under Water, Bradley’s first nonfiction book soon to be completed.

This is the second year in a row Bradley’s work has been a finalist at New Millennium. (See below.)

Written by Bradley Wester at 3:18 pm

Why I Hated Sasha Waltz’s “Kreatur” at BAM and the Arts Funding Econo-system

(Photo Credit: Stephanie Berger)

In Filthy Dreams, Bradley Wester critiques Sasha Waltz at Brooklyn Academy of Music, along with our system of arts funding and the art-star machine. Read HERE.

Filthy Dreams is a blog that analyzes art, culture and politics.Filthy Dreams is a project supported by the Creative Capital | Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant Program.

Written by Bradley Wester at 3:03 pm

June 30, 2018

FINALIST! for 45th NEW MILLENNIUM AWARD FOR NONFICTION — June 2018

Brothers Katrina by Bradley Wester is a FINALIST for the 2018 New Millennium Awards XLV in NONFICTION. This is the second honor for Brothers Katrina which won the Fresher Writing Prize for Creative Non-Fiction in 2016. Bradley’s story, along with all of the other shortlisted entries, can be found in the Fresher Writing 2016 anthology. It can also be read on line HERE.

Written by Bradley Wester at 1:39 am

Participant: The Writer’s Hotel Conference — June 2018 NYC

Chosen to participate in The Writer’s Hotel, a “Mini MFA” and one-of-a-kind conference! TWH Editors read and consult on each writer’s full length manuscript pre-conference, followed by a week-long conference in June. TWH NYC events are set at Midtown hotels: The Library Hotel, The Bryant Park Hotel, The Algonquin Hotel, The Roger Smith Hotel and The Casablanca Hotel. On site events include workshops, lectures and agent pitch sessions. And each writer reads their own original work at a landmark NYC venue: KGB Bar, The Red Room at KGB Bar, Bowery Poetry or The Cornelia Street Café. Faculty readings are another wonderful feature, and are held at Kinokuniya Bookstore and The Half King. From our virtual pre-reading process through to our NYC writers conference, TWH takes writers and their writing to the next level. Via TWH, writers bring their work from desk to marketplace at the heart of the publishing industry. It’s an extraordinary opportunity.

Written by Bradley Wester at 1:21 am

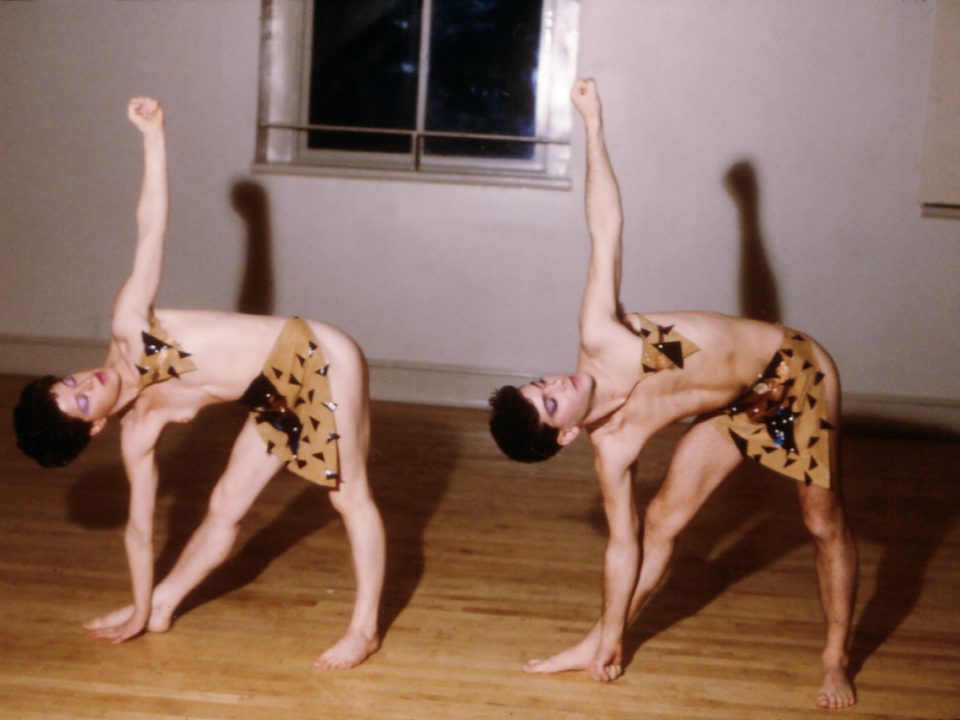

Bradley Wester reads GENDERFUCK at MoMA — March 2018

In conjunction with the Museum of Modern Art exhibition Club 57: Film, Performance, and Art in the East Village 1978–1983, this symposium explores the history and legacy of gender expression and performance in 1980s New York City. During this period of fluid experimentation, Club 57 was one in a constellation of post-punk social clubs, artist collectives, and galleries united by an interdisciplinary, collaborative approach to artistic production.

The symposium, Performing Difference: Gender in the 1980s Downtown Scene, will include screenings, panel discussions, audience dialogue, and a reception. Moderators, including writer, curator, and archivist Sur Rodney (Sur), performance artist and scholar Holly Hughes, and curator Travis Chamberlain, will be joined by performers, theater artists, and veterans of the Downtown scene to consider this crucial moment in the evolution of gender culture and its relevance today. Attendees are encouraged to come early to see the exhibition, an open screening of Diane Torr’s documentary Man for a Day, and a performance of Gender Fuck by Bradley Wester.

Written by Bradley Wester at 1:19 am

June 4, 2017

Attending NonfictioNOW 2017 in Reykjavik, Iceland

The NonfictioNOW Writers Conference is a regular gathering of over 400 nonfiction writers, teachers, and students from around the world in an effort to explore the past, present, and future of nonfiction. Panels and readings highlight the myriad forms of nonfiction, from the video essay and graphic essays, to the memoir, lyric essay, and literary journalism. 2017 Keynote Speakers: Karl Ove Knausgård, Aisha Sabatini Sloan, and Wayne Koestenbaum.

Photo: Karl Ove Knausgård

Written by Bradley Wester at 6:01 pm

July 6, 2016

My first Literary Prize: 2016 Fresher Writing Prize for Best Creative Nonfiction

“Brothers Katrina” is a true story of my brother and me—two estranged, polar-opposite adult brothers living in a tent for five days and nights on the front lawn of our family home just days after its near complete destruction by hurricane Katrina. Read it online HERE. It is a chapter of a larger narrative nonfiction book that I’m writing, titled “Growing Up Under Water”.

Fresher is a young publishing venture, established at Bournemouth University to nurture the publishing talent of the future and encourage new writers from across Dorset and beyond. The team is made up of staff, students and a wonderfully supportive executive board which includes Gemma Rostill from Penguin, publishing consultant Ed Peppitt and literary agent Madeleine Milburn.

Fresher does not currently publish unsolicited works, however, the annual Fresher Writing Prize gives new writers the chance to showcase their work in front of some of the best in the publishing industry, win some great prizes and, of course, to be published in an associated anthology.

Fresher Writing 2016 anthology can be purchased here or on Amazon Kindle

Written by Bradley Wester at 10:29 pm

April 7, 2016

Artist to Artist #4 (On the Occasion of my Guggenheim Rejection)

The conceit of the Artist to Artist series is a personal letter to a real person like in previous Artist to Artist #’s 1, 2 & 3. In this case, the piece began as a letter I sent to my Guggenheim Fellowship recommenders—those who wrote reference letters on my behalf.

Letter To My Recommenders:

Dear Recommender,

You are receiving this letter because you are a friend or colleague that holds the special place of being one of my reference letter writers; in this case, one of my Guggenheim Fellowship recommenders.

Choosing to be an artist and making it your number one priority for a lifetime—nearly forty years of this lifetime so far—might appear to be an insane enterprise. But for many of us, it is not a choice, but a way of being in the world. Otherwise why would we choose this path when, in these eleventh-hour days, being a true artist goes against the crux of contemporaneity as we have come to know it—there is no place for an art for art’s sake, or an art in service of change, in late market capitalism’s obliterating operation of supply and demand.

Not being in demand is the real state-of-the-arts for the clear majority of artists. The ambitious among us would like it otherwise, yet the ability to tolerate rejection might be the ultimate gauge of whether we are artists or not. Most of us, I believe, aren’t so much after the art-star-in-demand version we hear about, with her full-page magazine spreads, or his hobnob-ings with movie stars, or their waiting lists for bland inoffensive over-priced paintings. There are many artists whose primary ambition is to be a vital part of the conversation, which, beyond finding the means, time, and space to make work, means finding proper context. Sure, solid representation and a modicum of sales are important, but more importantly should the work be written about by smart writers, referred to in articles, discussed by other artists and art students, and be on the radar of smart curators who contextualize the work in important group museum shows, biennials, and surveys.

Going after the high-profile Guggenheim grant was just one of the ways I hoped would move my work toward its proper context. Context is everything for me these days. Context is what can transform my work from being a collection of smart aesthetic objects, ostensibly for sale, to the life’s work of a serious, thinking, passionate artist who is in meaningful conversation with other artists about the issues of our time. The problem is, without context, my side of the conversation has been hitherto suppressed. Even more frustrating for how deeply I am engaged in this theoretical, political, aesthetical conversation through the discovery and study of some of its best and brightest voices.

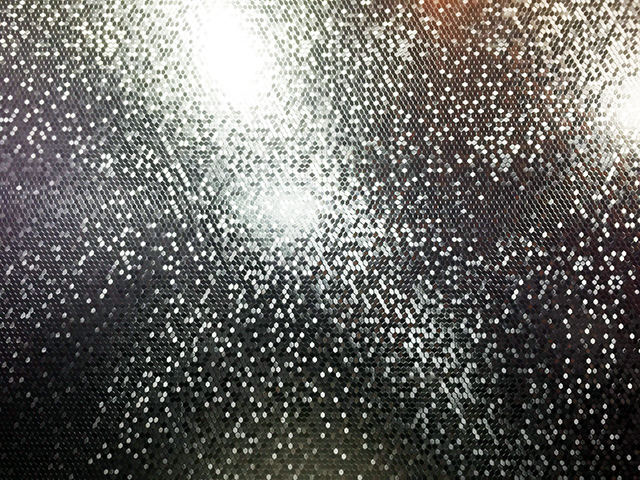

And speaking of brightest, and the desire to shine, the most serious concern of my recent work, as you well know, has been for the ‘politics of shine’. And it is through this interest that I want to join the conversation. These days, when anyone wants to disparage the inflated art market or our art-fair culture (and there is a lot to disparage there!) they describe the worst possible kind of art as ‘shiny’. While this is an understandable slur in this context, it has become a foregone conclusion. I’m interested in restoring the transgressive agency to shine, celebrating it while critiquing our contemporary shiny commodity fetish. Art does not have to be complicit with it. My mission is to put the disco back into DISCOurse

The beginnings of what I hope to be a larger article on the #shinegeist, (please use the hashtag) can be found HERE.

Part of my new strategy is to write my own context and do my best to get it out there. The paradox is that in the last four years I’ve made the strongest work of my career, and had two solo exhibitions. A review in Sculpture Magazine notwithstanding, it’s led to nowhere and I’ve sold less than in the previous fifteen years. Part of this may have to do with the limitations of the current gallery model, market forces, the mid-career artist who is not famous, and plain luck. Still, I have a lot to be grateful for—a more than respectable resume, incredible home and studio, awesome friends, and the freedom to focus my time on my work.

A lot to be thankful for, even on this day after receiving a form-letter from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation stating that I did not make the 178-person cut out of 3000 applicants, despite the extraordinary recommendation letters each one of you wrote for me. I get it. There are too many artists, and many of us are even good. And the funding and facilities of our granting institutions and residency programs are nowhere commensurate with the numbers of their applicants.

For me, the Guggenheim rejection marks #17 in a record 21 applications in less than a twelve-month period. Granted, more than half were writing related and writing is a medium for which I have less of a track record. Still, 17 rejections in a row out of 21.

What was it I said about the ability to tolerate rejection?

I’m choosing to let it roll off my back, and double down. There is part of me though that hates having to be responsible for this salesmanship aspect of my career, that hates having no other word for ‘career’ but needing to use it, and hates that we teach art students ‘professional practices’ these days. Yet I will say that reading, and especially writing, and the numerous efforts I make at communicating what I’m doing to get a grant or a residency, a job or a show, has more often made my work, and my relationship to it, stronger. Still, when a rejection comes, after all these years of experience and succeeding, there can be this voice:

“What are you doing wrong. You’ll never be able to ask for another letter again. Nobody likes a loser.”

I know several artists that simply can’t ask again because of this voice, even after one or two rejections. It’s a big ask, because it’s not the easiest thing for someone to jot off a letter, especially a sincere one, especially by someone significant enough to make a difference, and who therefore has been asked by others.

So, I want to thank you guys again, sincerely, for being in my corner, for believing in me, no matter the outcome. It’s difficult to express how important it is to have a few friends and professionals in their field recognize in my work what the larger world hasn’t yet. It’s confirmation, on those bad days when it’s not going well, that if my work has attracted the likes of you, I must be doing something right.

So count on it; I’ll be asking you for another letter soon!

Love, Bradley

April 2016

(Above image: “Conversation” (detail) drawing/collage, Bradley Wester 2016)

Artist to Artist #3 (Shine and its DISCOntents), made better by recent edits, and from which I will develop a larger article here

For other Artist to Artist entries and other writings, click on blog link at margin.

Written by Bradley Wester at 12:51 pm

March 23, 2015

Why I Left New York

Read my recently published article in the Providence Journal—the story of why I left New York for Rhode Island. This is not just another rant against New York and its turn against the creative class, but a real-life alternative story of creating artistic agency outside of New York City:

Letter from Bristol: Artist Who Left N.Y. Found Welcome Arms in R.I.

Written by Bradley Wester at 3:19 pm

March 11, 2015

Artist to Artist #3 (SHINE and its DISCOntents)

I use the letter format as I did in Artist to Artist #1 & 2. In this case, a letter to Tavi Meraud responding to her article “Iridescence, Intimacies” in the recent e-flux journal #61 entitled, The Politics of Shine. I wrote this letter concurrent with my solo exhibition, DISCOurse #2: SHINE at Pavel Zoubok Gallery in New York, 12 February to 14 March 2015.

Dear Tavi Meraud,

Your article, Iridescence, Intimacies, in “The Politics of Shine” edition of e-flux journal, and Sven Lütticken’s, Shine and Schein, have brought important insight and confirmation to my latest body of work entitled: DISCOurse #2: SHINE currently being exhibited at Pavel Zoubok Gallery in New York.

You write, “Iridescence…as a particularly scintillating instantiation of camouflage, literally dazzling the potential predator, is a demonstration of a particular interior-exterior negotiation that ultimately results in a suspension of the appearance-reality distinction.”

70’s to early 80’s Gay Disco is the point of departure for DISCOurse, its utopic impulse, the disco lights and their coincident glamorizing and democratizing effect over a space dedicated to marginality. By democratizing I don’t mean to make equal or banal, but that the disco lights make everyone equally exotic, iridescent.

You have me thinking in contradictions: To be iridescenced is to be camouflaged by diversification.

Camouflage, to hide in plain sight, can also reference the closet in the queer context, existing within society but undetectable, invisible to the straight hater-predator. The Disco lifted that veil of repression, even if only for a few hours, and it made queerness attractive, dazzling, even for the straight interloper—a rehearsal for inclusion.

Paradoxically the real diversity of queer difference and its essential demand for social inclusion was given only surface regard, if not suppressed, within many of the bar and club models designed for its expression. That is, bars in the ‘age of the closet’ were so often specialized or segregated by theme or type: Leather, S&M, Twink, Professional, Hustler, Drag, Go-Go, etc. They may have celebrated the agency of a radical lifestyle, but also promoted a brand of conformity. For me that period’s greatest limitation was how it reduced us to one common denominator—I could never abide ‘hooking up’ with someone simply because we shared the single trait of same-sex attraction, no matter if that attraction was the desire that got me to the bar in the first place.

The Disco however, save for its consistent disco beat, was a sea of sparkling variation for all the types described above and more, including straights—from an S&M leather man to Andy Warhol, from movie stars to art stars, from drag queens to Jersey teens—the original glitterati. Freaks of all sorts were especially guaranteed admission. Not to disavow the elitism of the eventual velvet rope, but for a time the Disco was a dreamland of marginal belonging.

With my new work, DISCOurse, I attempt to both celebrate and critique our contemporary shine fetish by putting the Disco back into the discourse on shine.

Is there something deeper beneath the shallow of our contemporary fixation with the shiny object?

Shine is both thin and impenetrable, its depth is an illusion, all smoke, and mirror. Shine flatteringly reflects our own image literally inside our things, as well as the image of others watching us watch ourselves inside our things. Shine makes us look good. Alas, it is opaque. Shine is stealth, an apparatus that obscures. Whether masking our own mortality, the politics of labor production, or the destructive force of a drone, shiny is the preferred characteristic of our neo-liberal market economy of things. Accordingly, our shiny commodity fetish acts to distract us from, and formally condition us to, an habituated environment of omnipresent surveillance and secrecy. The more we embrace it, the more we are made in its image. No longer discerning customers, but drone volunteers made featureless via ‘mirror marketing’.

So you would have to be crazy to make shiny art if you want to be taken seriously. All too often we hear or read commentary about the inflated art market and the rich spec-u-lector’s crass taste for the “new and shiny”:

“The auction houses have seized on the phenomenon of wider interest, and, coupled with dwindling supplies of Modern and Impressionist works, have shifted their emphasis to the sexier, publicity-generating field of the endlessly new and shiny.” —Kenny Schachter, UBER ART, March 2 2015

This is only one example of the oft pejorative use of the word shine or shiny when referencing contemporary art. Paint something silver and it instantly looks contemporary and goes with anything. And who was it that first said, “If you can’t make it good, make it big. If it doesn’t look good big, make it red. If you want it to sell, make it shiny.” So many contemporary artists do just that, and there are collectors who are willing to buy it. But is there more to this shimmer than meets the eye?

The Disco Ball, a recurring object, and referent in DISCOurse is the perfect seductive yet transgressive shiny object to address today’s Shine-geist. A spinning disco ball with its fractured surface of reflective mirror ‘fails’ or breaks our image into a multiplicity of moving reflections in the round that are then scattered onto limitless chance surface-shapes—dizzying, exotic, ‘queer’ mirror, a pixelated globe of potentiality. Here, even the straight reflection is made queer.

Industrial pegboard, another material found in DISCOurse’s hybrid practice of installation/sculpture/digital-image/and painting, allows me another strategy to have my way with shine. Like the disco ball as analog pixelator or image-failing device, the pegboard, which I custom coat with reflective Mylar, literally looks like a computer motherboard, and becomes the conductive substrate for other recognizable materials that are fixed, connected, like circuitry, but with unfixed associations. Here then is a mirror that is a representation of 1’s and 0’s, a shiny dot matrix which includes our now rasterized reflection, that we literally see through, sometimes to another layer. So a tri-spatial phenomenon of the viewer, their actual space, along with their reflection in the screen of Mylar’d pegboard, and finally the space that we see through, to the other side of the pegboard.

In the ‘Screening the Surface’ section of your piece, you speak of a related but different kind of tri-spatial phenomenon when referencing the virtual and real spaces that screens occupy or are occupied by—screens that hold projections as in film, screens that act as barriers or blockages, and finally screens as in computer screens:

“Oliver Grau’s suggestion that the spectator of a computer screen is in fact in three different places at the same time: the spatiotemporal location of the viewer’s body, the tele-perception of the simulated space, and tele-action that happens when one manipulates a robot’s [drone’s] actions with one’s own movements. This multiplicity—or more specifically, this simultaneity—of being present in multiple realities suggests that the key issue here is reality and how it is defined, staged, and refined.”

Mimicking the form factor of computer circuitry, my pieces also become literal screens, that both obfuscate and illuminate what stands between the here and there, the now and then, present and future.

I am now considering other significant associations embedded in my use of generic commercial pegboard: as both a holder and organizer of tools used in manual labor and as a display-holder of commodities in thrift store aisle constructions. Both uses are conflated in the DISCOurse works, and together they become their own commodity in the form of an artwork. And finally, by metalizing this uniformly perforated material, it not only mimics the form factor of computer circuitry but also suggests the chink in neo-liberal’s armor.

Celebrating the imperfect, the perforated, and the broken shine, I reveal the interstices of societies’ reflection, the spaces in-between, androgynous spaces, where potentiality lies. The site of DISCOurse, like cross-border economies, is where ideas and materials are hybridized and repurposed, where culture, commerce, and the imagination anticipate a future diverse: queer time.*

Oh, and it’s more than, but a little bit: I’m gay and shine is my territory—a rich, deep, anything but shallow terrain. Hello. Snap!

DISCOurse #2: SHINE at Pavel Zoubok Gallery in New York through March 14th, 2015.

Sincerely,

Bradley Wester

* Special acknowledgment and thanks for José Esteban Muñoz’ book, Cruising Utopia, the Then and There of Queer Futurity

Written by Bradley Wester at 2:47 pm

July 11, 2012

Artist to Artist #2 (informal thoughts on recent symposiums)

The conceit of the Artist to Artist series is to use a personal letter format to a real person to place current art theory, practice, and/or exhibitions in relational context with one another in real time. In this my second iteration, I write the contemporary art historian, Ann Albritton, friend and former colleague, about various related symposia and art writings that I have encountered over a period of a few months in 2012.

Biennale de Lyon, 2011

Dearest Ann,

I’ve been attending lots of seminars and talks here in New York lately and they have me thinking. Missing you, I will lay down some of my thoughts, pretending we are still near enough to continue this conversation over one of our long and interesting dinners. One seminar, hosted by the New Museum, was called, Independent Art Spaces Symposium. Reps were there from spaces and ‘non-spaces’ around the world including Korea, Cairo, Mexico, Miami, and New York discussing just what constitutes alternative in an institutionalized world. Much came down to money and survival, and the discussion of labor with regard to exploitation of artists and staff. It was noted that many alternative places especially in the 2nd and 3rd world are alternative by default, some in competition with one another rather than fighting the same fight, some wanting ultimately to be part of the establishment. In the U.S. it seems difficult to avoid institutionalization. Artist Space of New York was represented as an original alternative space, but one that has made its institutional compromises in order to survive. Participant Inc. clearly has the integrity of an alternative space, and so the lack of money and bare subsistence.

I met an artist on one of the panels there, Deana Lawson, photographer. She ‘inherited’ a very non-traditional artist discussion group called 6-8 months from Kara Walker. She’s renamed it 68 months, again so it never becomes institutionalized, and she represented a different kind of alternative space, one that doesn’t even exist until people are gathered, more of a salon really. It’s simply a loose group of artists, academics, historians, musicians, a chef, etc., that meet to discuss a topic, text or idea. It will only last a period of 68 months, before it is handed off to someone else I suppose. Deana invited me to the most recent gathering, hosted by another alternative space called RECESS in Soho.

The text we were given in advance was about China’s influence in Africa, demanding collusion in squashing any kind of dissent that threatens their interests there. How do we define or create space for dissent in an age of advanced government sanctioned silencing? Much of the conversation came down to what role art plays in this. Is art a space for dissent or has it systematically been muted? James Baldwin was quoted on the role of the artist. Some of us in the room were uncomfortable with his “grandiloquent claims” for the artist and the artist’s responsibility to society. It was pointed out how times have changed since those words were written, before Kennedy and King’s assassination even. In our post-cold war, post-9/11 world, a world that is touched in its entirety by ‘late’ market capitalism, with an art world fed more and more by institutionalized MFA programs, Baldwin’s words seem at best nostalgic for a simpler, poetic time. We talked about whether we have that much faith in art today. Some said they didn’t. During Baldwin’s time, art seemed quite naturally a space for dissent even when it was not directly political, because it was ‘other’, because it stood on the outside, was made in the margins. But is there an outside today?

Related to the symposium on independent art spaces, our conversation was about trying to define the (alternative) space for dissent, and wondering if one still exists. Baldwin suggested such a space existed when he wrote that what separates artists from other people is our cultivation of aloneness, which most others avoid. I thought of social media and its impact on artists and the art world today. We are so connected now. We are all on the inside. Writer/curator Dieter Roelstraete skillfully examines this notion in his excellent article: On Leaving the Building: Thoughts of the Outside. Our inside-ness may have rendered us afraid to be alone, even if our sense of belonging is only virtual, but I’ve come to realize that it is from the inside we must act. There may no longer be agency from the outside (a la Baldwin’s aloneness) if an outside exists at all. Does a falling tree make noise in the woods if no one’s there to hear it? The myth of the solitary genius alone in his studio has been deflated for some time now, made apparent by the prevalence of socially engaged and political art coming out of leading MFA programs. 68 Months was indeed an interesting evening for me, to be out of my normal circle, and, incidentally, to be in a white minority. I’ll go again.

I was later at another symposium, speaking of the outside, called “We Who Feel Differently,” also at the New Museum, on gender difference and the state of queer politics. There, an academic/activist named José Esteban Muñoz called for a “de-hierchicalization of difference”, a “shared indignation” and a “critical hope”. He talked about the true ‘commons’ as not a place for consensus but one of conflict and turbulence. There was lots of talk (and this was a couple weeks before Obama came out for gay marriage) that the gay right to marry is in part the “heterosexualization of queerness” which leaves out, even hurts, the messy queer edges: transgendered, mix-gendered, radical fairies, ‘hardcore’ drag queens, S&M, promiscuous, etc. Another gay writer, scholar, playwright and friend, Sarah Schulman, wrote on her Facebook page minutes after Obama’s announcement, that it is not gays who’ve changed the majority but the majority who’ve changed us. In the resulting discomfort and shame of the AIDS crisis, we have volunteered to be normalized, losing our once radical voice and utopian impulse to change the status quo. So we find ourselves on the inside of a hetero-centric institution called marriage. While this has been the objective of the LGBT lobby and its leaders for some time, I’ve never been comfortable with homo-normalization, and feel invigorated by these voices. “We Who Feel Differently” was a symposium that seemed to call for a new radicality, a way of reclaiming the potentiality of queer space, even if it is now on the inside.

Since writing this I’ve bought and read most of José Esteban Muñoz’s excellent book, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity. He thesis hinges on the work of several queer writers and artists, especially O’Hara and Warhol, Jim Hodges and González-Torres, their essential hopefulness and the importance they place on ephemera and the everyday. It gave me insight into my own work; clearly I’m heir to this line.

About a month ago I went to the e-flux gallery/reading library on the lower east side for a panel discussion on: Critical Knowledge Production in Art, Science, Activism, with Maria Elena Torre, Public Science Project New York, Oliver Marchart, political theorist Vienna and Lucerne, and Danna Vajda, artist and writer New York, moderated by Nora Sternfeld, ecm Vienna. A week after that I spent the afternoon watching a live feed of the 3rd FORMER WEST RESEARCH CONGRESS in Vienna. Both focused on ‘research’ and ‘knowledge production’ in the fine arts and its relation to the political: “Is Contemporary Art—art in and of the epoch of neoliberalism—on its way out, together with the system that made it possible?”

Wow. Is this an academically sponsored attack on contemporary art, as we knew it? Or a timely re-examination of art’s relation to the world supported by arts natural predilection for change?

Marchart from the get go divided art production into two parts, mediated and non-mediated, and only spoke to art that mediates, making the assumption that all of us present were interested that kind of art only. By mediated he meant art that is of the political kind; unmediated art (art who’s main concern is aesthetics and form) was likened to “navel gazing”, a phrase often repeated throughout the evening.

I am certainly not interested in an indulgent art as the term “navel gazing” implies, or in art as a luxury commodity either. I’m attending these talks, reading these articles, because I am experiencing a fatigue with, and slight suspicion of, work that merely offers yet another version of aesthetic, formal, or anti-form manipulation, no matter how seductive and engaging. And I’m tired of abstraction, figuration, or pop-surreal redux without a radical contextual change. Yet, as much as I am passionate about and influenced by the politically charged theory I read of late, I also have little tolerance for the ‘reading-library–as-activist-art-exhibit’ or for “Aesthetic Journalism” as art, both de rigueur formats of elite MFA program graduate shows and prominent international exhibitions. They bore me to tears.

“Artists are here to disturb the peace.” —James Baldwin

There is clearly a sea change taking place in the art world. Think of Baldwin and that era of artist in America. And now with what looks to me like two divergent even antagonistic directions in art practice today that, like in other times in art history, pit the future against the past: a political and socially engaged art vs. an aesthetic and studio driven formalist art.

It is easy to find fault with the aesthetically driven kind, when this work can so easily be co-opted by a commodity-driven gallery system. The vulgar distortions of reality perpetuated by the more and more exclusive A-list galleries, art fairs, auction houses and their cult of super rich artists and collectors is how most laymen see the art world. How many hundreds of millions now paid for the most expensive artwork sold at auction? And the many overpriced art schools here in America must perpetuate the fantasy of “get an art degree and become a rich and famous artist” to rationalize rising tuitions in a shrinking economy. Meanwhile economic and political systems fail across the globe. Is it any wonder art’s role is being reconsidered?

In Europe, where there is still a moral imperative to keep market forces out of education, we find a greater sympathy for and abundance of political and theoretical approaches to art, and this in turn has influenced our elite and more academically oriented art schools here. This kind of work could afford to exist in Europe separate of the market thanks to generous state subsidies. Governments there have historically supported their academies, their cultural institutions, and the artists themselves. What looked to me like utopia from this side of the Atlantic during the 80’s—such support we never had in the U.S.—now looks like an incestuous condition for the insular looping of ideas, and grounds for its critique. Has art of this kind in Europe lost touch with its audience, become too academic, too esoteric? Has it become elitist in spite of its good intentions to work for change and the greater good? Whatever the case, the current economic and immigration crisis across Europe, and the resulting budget cuts and conservative policies, will have no doubt both a positive and negative impact on this.

Surely one of art’s unchanging characteristics, or charges if you will, should be to disrupt ways of seeing, therefore ways of knowing. Here I can almost understand Oliver Marchart’s (at the e-flux Critical Knowledge Production talk) replacing ‘critical’ for ‘political’ knowledge production, since the political left has historically attempted the disruption of systems toward change and justice through activism. However, after it disrupts, art, unlike political activism, should not be responsible for the specifics of knowledge production nor for its organization, but rather only for the initial (and continuous) disturbance—the un-ordering of the ways in which we think we see and know. This ensures that art will indeed look very different to us in the future, but its basic operation the same. Otherwise, art making becomes a very arrogant and pompous thing.

Marcuse’s critique of Marxist aesthetics, encountered during my MFA Thesis research, will always stick with me: That so-called art that stands in opposition to something is horizontally equal to that which it opposes. Art must rise above opposition (not in the elitist sense), remain autonomous and therefore free of all authority but its own. This is art’s sole distinguishing factor from all other human work, and therefore its most radical characteristic. In this way, art is political. I know the ‘autonomy of art’ debate is valid, but I’d like to revisit it. The challenge is to create an autonomous art that is not vulnerable to cooption, not throw out the idea altogether. Art’s definition then should begin with its disruption of our field of view, then continue by influencing the knowledge producers who follow.

Art is the ‘avant garde’ of political activism, that which comes before it. Artists may in fact be the original “organic intellectuals,” as Oliver Marchart defined political activists who became knowledge producers by default. So artists are not knowledge producers so much as knowledge catalysts.

Relevant to this debate, is another article I just read by the artist Nada Prlja, born in Sarajevo, with the somewhat confusing title: The mimicry of artistic practices is not a novelty – why art institutions still lack a method to support this phenomenon? She claims, and I agree to a large extent, that there is a discrepancy in the international art world, where artists now are like secretaries taking notes from the powers that be on hard to understand concepts, trying to keep up but ultimately feeling out of the loop:

“… marionette’s threads [that] are being pulled by the curators/educators/institutions. It is they, rather than the artists, who are providing the marionette (the artists) with a voice and directing its movements, in their desired directions.”

Prlja goes on to describe a rather binary view of politically oriented art production: art that simply observes and represents ‘designed to fail’ conditions, and art that is oppositional to, and takes initiatives against, ‘designed to fail’ conditions. These are rather depressing choices. We must be either journalists or activists it would seem. Either way, it risks an arrogant ‘artist knows best’ syndrome. Aren’t there conservative assholes out there that might also be great artists whose work might contribute to social justice in spite of themselves? Who are we as a group to be so good intentioned, so politically correct in our subject matter?

It all comes down to a crisis of faith I sometimes think. That’s faith with a small ‘f’ and not a return to Modernism with a capital M. (Baldwin?) To have faith in art today is not easy when global neo-liberal economic forces cannibalize everything, even activism, and turn it into a product for sale and profit. (See the MacDonald’s “It’s your lunch, Take it” ad campaign and how it coops the Occupy movement.) I see this as a complicated transitional moment for art that is neither a full rejection of the (failed) utopian modernist legacy, nor a full acceptance of a neo-Marxist activist mandate. In these precarious times, the overtly political makes a kind of sense. But could this impulse be too safe, over-intellectualized? Most of us agree, at least on some basic level, that art is in service of change. But does that mean art is activism? Some will argue, myself included, that art is art because it works on subtler, more mysterious levels. Maybe we need a leap of vision. Either way, art must remain art. And by that I mean it must distinguish itself from what is not art, which is everything else.

Prlja’s entire “Designed to Fail” thesis and her two modes of artistic production, much like Marchart’s favoring mediated over unmediated art, might be seen as a reactionary attempt to rectify a crisis of faith in art by forcing it’s social relevance. I propose that there are three key conditions and limitations imposed on contemporary art today that contribute to this crisis: 1) What I will call the rectification of arts social status, which I suggest Prilja and Marchart to be involved in. 2) What Prlja calls the “ritual of mutual legitimation” between artist and curator. (The marionette strings.) 3) What Jan Verwoert calls “conceptual self-justification”, what many of us post-conceptual artists feel compelled to do—justify our every creative move. (See Verwoert’s excellent article, “Why Are Conceptual Artists Painting Again? Because They Think It’s a Good Idea”.)

This triangular need to rectify, legitimize, and justify—certainly does not sound like what art or artists are supposed to be doing. It sounds more like an echo of the very system that art by its nature should stand against.

OK, gotta end this and make some art.

I love and miss you!

Bradley

Reply by Jaimie, Submitted on 2012/07/12 at 1:20 pm

Art’s definition then should end after its disruption, but continue to influence the knowledge producers.

Art both has no definition, and has the definition of having no definition. It exists in the place of opposition, exists in the place of bringing together that which does not wish to be unified. It is like the alchemist, who smiles while mixing that which would never have mixed, and using it as a method by which he can demonstrate to both the material and the observer that their conceptions of reality are little more than reassuring illusion. It wishes to break and build simultaneously. It wishes to make uncomfortable, it wishes to provide additional mirrors, it wishes to create destruction and growth. It cannot end. Art has no definition, and has the definition of having no definition, and thus is exempt from the concept of beginning and end. The universe itself is art, is beautiful, is infinite, is forever, is chaos. The Everything, from the smallest fundamental building block of matter to the largest cluster of galaxies. That which makes it art is the presence of a deciding factor, the presence of the curator, the presence of a conscious (or semi-conscious) species, the presence of presence itself. Thus, the beginning or end of art is only a mirror, reflecting the beginning and the end of the curator, which in grounded terms is the beginning and the end of humanity. Thus to say that art is influencing the knowledge producers is a tautology, being that art is an extension only of us, the curators, and that the knowledge producers are another arm of us, the curators. We influence ourselves. Art, the infinite, the chaotic, influences Knowledge, the finite, the harmonious. No human, no curator, can be placed in only one category.

Maybe artists are not knowledge producers so much as knowledge catalysts.

Yes, maybe artists are not knowledge producers. Indeed, they make no claim to permanent knowledge, other than the knowledge of what has already happened, and still they bicker about the inability to separate context and interpretation from event regarding this knowledge of what has already happened. Knowledge, the finite. That which can know everything and still know nothing. Knowledge is the very root of the capitalist doctrine. What is knowledge? What is this pursuit? It is the desire to accumulate, the desire to produce surplus, the desire to create a repository of things which may only be useful for a short time and take a great deal of energy to create. The search for knowledge, the desire that more or better be produced, is exactly the fuel that creates the capitalist institutions that art resists so vehemently. Art then, has not been subverted, but has subverted itself, to be the driving force behind that which it resists. Which of course makes intuitive sense, as that which focuses on having no definition needs something to have a definition to distinguish itself from. La Différance, the need for an opposite to have a definition. The price for art and resistance to exist is something to resist.

I am interested in the word catalyst. A catalyst needs the materials of the reaction to exist, prior to becoming. It is not required to exist, as the situation would carry on without it, though the situation would not be as efficient or beneficial. The catalyst itself is useless without the exact scenario that it can improve. It is a molecule that exists only to enhance others, and has no purpose otherwise. If one is born to help, and only help, and have no purpose otherwise, is one angry? Servant, Slave, No life of ones own, except to improve others. Is this better, worse, or indifferent? Higher, lower? Equal?

There is something else here, the combination of the concepts that art is a catalyst and is not needed to exist, but that it accelerates the processes of capitalism/knowledge because this is the only way it can exist. Ah, I see. It is choice. Art chooses to be the catalyst. It chooses to make the situation better, or worse. It wishes to accelerate, maybe for no other reason than to expose direction and create excitement.

A catalyst must choose to exist. whoa.

This need to rectify, legitimize, and justify—certainly does not sound like what art or artists are supposed to be doing. It sounds more like an echo of the very system that art by its nature should stand against.

Rectify, legitimize, justify. More of a courtroom than an art discussion. Or is it? We have come to a place where the definition of art has blurred to the point of complete ambiguity. It is everything and nothing. A brilliant artist in their retreat, creating true masterpieces but who never shows them, or a Hollywood celebrity who creates poster art for mass consumption and sells the junk and the originals to collectors in their massively overfunded upper echelons. Are they existing in the same definition? How can this definition be reclaimed?

Well, by accelerating, of course. Accelerate directly into the sun, into the black hole, into the death. Rectify, Legitimize, Justify. Art desires suicide. Phoenix, zombie, or deity will arise, and maybe all three. I say give it a push. I choose to be a catalyst.

Reply by Michelle Standley, Submitted on 2012/07/13 at 5:56 pm

There’s so much here that one could comment on. But to pick one: I want to add a second voice of support to your comment, ‘I have little tolerance for the ‘reading-library-as-activist-art-exhibit’ or “Aesthetic Journalism” as art.’ I share your frustration. How might art provoke dialogue with those who stand outside the circle of theory-informed elites? Loads of explanatory text ain’t the answer, that is for certain.

Reply by Bradley Wester, Submitted on 2012/07/16 at 6:12 pm

To Jamie (first comment above), my Quantum Philosopher—

I’m just amazed at our collisions. How is it that this artist found a Quantum Mathematical Philosophy nerd, who is a natural poet, to collide with? Thanks so much for your brilliant riffs on my blog entry.

A few words on your words, (Double quoted words are mine from the article, your words are quoted, unquoted words are mine written now—The blog won’t show italicized or underlined or bold words):

““Art’s definition then should end after its disruption, but continue to influence the knowledge producers.””

Of course, ‘Art’ is ultimately undefinable, in that it can be anything, impossible to know what it could be next. And I do essentially believe that so long as an artist calls it art, it is art. I mean, please, do we (not you and me, but the Royal ‘we’) still need to argue Duchamp? There is no place for the “But is it art?” argument, or “My four year old nephew could do it” anymore. I suppose I am trying more to get at what art ISN’T. But if anything can be art, then do I have the right to say what isn’t, even if an artist or curator is saying it is? Maybe I’m questioning if there isn’t something new that has developed, an artistic, research-knowledge-based activism (aesthetic journalism?) that should have its own name. But not the Art name. Because I am arguing I suppose for art’s autonomy.

Even what Duchamp did by choosing and hanging a urinal in a gallery, was to de-contextualize it, therefore free it from its meaning and usage. Did he not ingeniously and brilliantly make autonomous the everyday? So radical and yes, political. He changed everything. But it’s how he did it that makes it so, I don’t know, how do you nail a thing like art down. Of course we can’t all be Duchamp.

Also to clarify: There is much to-do these days over the relationship between artist and curator. One debate is that the curator thinks him/herself too much like the artist, and/or one who appropriates the artist’s work for his/her own agenda. The argument is, should it not be the artist and the artist alone that says, “this is art, and this is its context.” And then there is the article I quoted, the case of curators and academicians manipulating the strings of the artist marionettes. This I believe to be true and disturbing, at least in part.

““Maybe artists are not knowledge producers so much as knowledge catalysts.””

“Knowledge is the very root of the capitalist doctrine.”

“Art then, has not been subverted, but has subverted itself, to be the driving force behind that which it resists.”I believe that what you say here is a serious negative. Do you? Are we agreeing? I get to that point in the next section when I say:

““This need to rectify, legitimize, and justify—certainly does not sound like what art or artists are supposed to be doing. It sounds more like an echo of the very system that art by its nature should stand against.””

But what do you mean when you say:

“La Différance, the need for an opposite to have a definition. The price for art and resistance to exist is something to resist.”I am saying, that is Marcuse has said, that art should not exist on a direct opposing, horizontal plane, for it therefore would be horizontally equal to what it resists there. ‘Art against domestic abuse’, for example. Should/can art be that precise, so targeted, so moralizing?

Do I really want answers to these questions? I love the grays of meaning that arise when I read you. Too often I want a black and white answer. As usual you turn me upside down and I see new meanings and possibilities.

So you have reminded me that while art does not do well with horizontal resistance/opposition, it does indeed need resistance in order to come into existence—Its natural resistance to the status quo, to the Kantian ‘fear and anguish’ of the human condition perhaps, to injustice in the broadest sense, even though a specific injustice may inspire it.

“[A brilliant artist creating masterpieces, the poster artist of mass consumption…] Are they existing in the same definition?”

I know you are not an artist, and have probably not seen as much of the art and exhibitions I’m questioning here. So: I am starting from an assumption of sorts, that there is a difference between a ‘contemporary artist’ and a commercial artist, and a difference between a contemporary artist and an artist who happens to be making art today. A ‘contemporary artist’, for the purposes of argument, is one fully engaged with her place in the world and his relationship to and awareness of art history, such that it is—a linear narrative, false and full of holes. The vulgar way of putting it is that there is a difference between a ‘serious artist’ and a commercial artist, a difference between a ‘serious painter’ and a ‘Sunday painter’. Yet of course a commercial artist and/or a painter who only paints on Sundays could indeed be a brilliant contemporary artist. (Another necessary contradiction.)

“How can this definition be reclaimed? Well, by accelerating, of course. Accelerate directly into the sun, into the black hole, into the death. Rectify, Legitimize, Justify. Art desires suicide. Phoenix, zombie, or deity will arise, and maybe all three. I say give it a push. I choose to be a catalyst.”

I’ve been saying all along that the systems failing all around us are failing because they need to fail. ‘Bailing out’ the failing systems is not working to save them, and will make the ultimate fall from much higher, thereby faster—Acceleration!

“Rectify, Legitimize, Justify. Art desires suicide. Phoenix, zombie, or deity will arise, and maybe all three. I say give it a push. I choose to be a catalyst.”

So let it happen? Art’s suicide? Is that what you are saying? Let the rectifiers, the legitimizers, and the justifiers, rectify, legitimize, and justify, so the faster it will fail!

Am I a catalyst for failure? Is that the point, for art to help the ‘knowledge producers’ move toward failure, be lucky to fail? Are we describing arts utopian function, to destroy what has come before for something better? Can this be done without a moral component? Is art autonomous then even of the moral?

I think it has to be, in order for it to be truly revolutionary.

Comment by Sarah Petersen, Submitted on 2012/08/21 at 6:02 pm

Bradley, I agree with so much of what you’re saying here. Any attempt to rectify art’s social status, by art, seems like such a tiny endgame. I do still appreciate art’s attempts to rectify other situations, and I do think, as artists, that’s part of what we can do. I’m reminded of the review on this year’s Berlin Biennial by Jakob Schillinger in the summer Artforum (which you’ve probably already read), the final line of which reads, “The question (posed by the curators in a recent issue of Camera Austria), What can art do for real politics? might actually serve a different interest: What can politics do for art?” The ever-legitimizing, amorphous blob that is the art world, always ready to incorporate anything cool into its massive body, seems now to be legitimizing itself through mere proximity to actual political revolutions in which people risk their lives to make change happen. I have to ask myself this question – quite seriously, am I doing this, too, in my art practice? Just out of grad school and finding time to reacquaint myself with active participation in the political world, I still wonder (and don’t know) whether a more tidy compartmentalization of politics and art (separate but equal?) might not work much better than trying to accomplish one with another. I do remember Ranciere convincing me of something similar in the last year…. And yet, at documenta this summer, I still found myself most struck by and appreciative of those artists attempting to use art as a mirror for politics and its consequences. That’s the work that’s stuck with me.

Also, I agree that art’s best aim might be disruption and interruption, influencing (rather than assuming the robe of) knowledge producers. Perhaps there is another angle, though – I think about Janet Cardiff’s pieces, how she uses historic site-specificity to create not just awareness but empathic response. Adrian Piper, too, is such a master of this; the informative shock and the empathic feeling come simultaneously when you’re with the work. I hate to sound like a 19th-century school marm, but I still think part of what art has always done for humans is create an awareness of others’ plight that’s not about statistics and the news but about empathy. Sometimes artists get the elements of the equation totally wrong – we’re “interpreting,” after all, not merely representing the facts (that’s part of our zone of freedom, right?) – but the result, even when based on flimsy, first-person analysis, can still be profound and necessary on the receiving end. It’s strange to talk about this ethical element of art making, because I think many of us feel really uncomfortable taking it on as a place to make work from – it does sound retrograde, and we have to maintain the freedom to be wrong, selfish, experimental, whatever. A lot of “systems-based” work from the 70’s (and after) seems to be hiding its motives from the safety of obscurity but still motivated by just such an empathic break-through. How embarrassing! And humane! But I think that, now that the formal shocks of 20th century art movements have done what they can do, we’re left with now, with next, with who, with where, with what’s up, rockers? What IS up? I think many of us can’t comfortably compartmentalize our responses to What’s Up along aesthetic and political lines, anymore. Personally, I feel like there’s maybe not enough time left (or name your favorite endangered resource) to isolate these responses from one another. When people want to know what I think of Occupy now, I want to say, Let’s talk about what Occupy was talking about, not about Occupy. I can’t comfortably go meta, anymore. The game is still on.

Written by Bradley Wester at 4:51 pm

January 8, 2012

In Memory of de Kooning, or Noguchi Yellow

I ran to MOMA this week, last minute, to see the long overdue de Kooning a Retrospective, which closes on Monday. One of the earliest painter-heroes of mine, I couldn’t miss it. And it was wonderful.

As I entered the final room of the MOMA exhibition, I stood before the wall with three of the late paintings, circa early 1980’s, looking for the painting I stood before in 1982 when I met Mr. de Kooning at his home in Springs, Long Island. What I noticed was a dominant warm yellow color in them. I looked around, and many of the late paintings seemed to be concerned with this particular yellow in or next to expanses of white. Then suddenly I remembered a humorous detail of that magical evening when I met Mr. de Kooning that now, in front of his late paintings, appeared to be strikingly significant.

So I pulled out an article I wrote about that meeting, in his memory, the year he died. (It was published in the modest but valuable REVIEWNY that Bill Bace used to put out in the Soho days.) Remember the colors yellow and white as you read this article below:

In Memory of WdK, 1997

I had the good fortune and honor of meeting Willem de Kooning in the early 80’s. I was fresh out of graduate school, still then a performance artist, but only a few years from deciding on painting as my right medium. We met at his place on Long Island for dinner. Swordfish. Cooked by his wife Elaine, who had returned to care for him after he had finally stopped drinking and was ‘going down hill,’ or so they said. He was still painting at the time, and there was a mess of painting and drawing going on in that famous studio of his. I arrived with Robert Wilson, late of course—to my horror, not to Robert’s. We had actually missed dinner, and Elaine had to cook what she had saved for us on their massive restaurant stove. There was one other person there, some major New York socialite whose name I forget. (She’d be mortified.) It was her that set up the dinner for Bob Wilson’s sake. I remember Bob telling me once that his three greatest inspirations were Willem DeKooning, Barnett Newman, and Ballanchine. Joe Cocker was up there too.

Anyway, the latest Noguchi lamps had been sent to the de Kooning’s, by the socialite I think, some time prior. Noguchi was still alive then. She, the socialite, noticed in polite disgust, that someone had put yellow bulbs, “of all things,” into the pristine paper-white lampshades. Well the two women were a twirl finding new white bulbs to replace the yellow ones. Bob and I were on the couch watching TV(!) with the pale, saintly, Bill, who had the deepest, iciest blue eyes I’d ever seen, when the socialite and Elaine stood between us and the TV screen: “Dear dear! Oh no! Did you put yellow in the white Noguchi’s? Oh dear dear, only white bulbs are meant for the Noguchi lamps, you see? Look how much better! Dear dear.” Bill tried in vain during his admonishing to turn the too-loud TV off with his remote control but couldn’t because the women were obstructing the beam. The moment they moved away, the TV popped off. Loud silence. Bill de Kooning, a bit sadly and sweetly, said to the women’s backs, “I liked the yellow.”

Later I asked him if I could have the privilege of entering his studio. He gladly let me in to roam alone the piles and splatter. Scribbles and sketches everywhere, that I touched, handled, even stepped on. Oddly, what impressed me most—I was not then so fond of his later paintings—was how he worked, and the layout of the place: the ship’s prow of a viewing balcony jutting into the studio high above, and the worn spots on the protected paper-covered floor where he stood most often, always in relation to the painting being worked on. The spot close to and just to the right of center of the large canvas on his famous tractable easel that could drop the painting below floor level in order to paint the top; the spot left of that where he mixed paint on his enormous work table with its own topography and architecture evoking painted histories; the spot yards in front of the canvas where he stood at a distance, between passages of painting, to see where he or the painting was heading; and the worn spot further back still, for relaxed contemplation, at the foot of his heavy Dutch rocking chair with wide paint-stained arms. And the paint-stained coffee mug resting on the small table separating his chair from the other like-chair to the right, cleaner and with no worn spot at its foot—the guest’s chair, the dealer’s chair, Elaine’s chair.

I sat in his, touched its arms of still-wet paint, looked at what he saw, then walked the runway between his chair and his painting, awestruck, standing in all his spots.

—Bradley Wester

For more Architectural Digest photos of WdK’s Springs home and studio, click HERE.

Written by Bradley Wester at 5:12 pm

May 6, 2011

Artist to Artist #1 (informal thoughts on current exhibitions)

Considering the exhibition “EYES WIDE SHUT” in relation to the following two articles:

Boris Groys

The Weak Universalism

Hito Steyerl

In Free Fall: A Thought Experiment on Vertical Perspective

EYES WIDE SHUT

Cheryl Donegan

Tom Meacham

April 14 – May 22, 2011

Nicelle Beauchene Gallery

Two Aerial Artists, a Falling Duet by Bradley Wester

Dear Cheryl,

Thoughts about your exhibition with Tom Meacham at Nicelle Beauchene, and its press release—a run-on description of the actual hanging/installation of the show, with precise spacing and measurements for the art’s placement, but with no description, explanation, or regard for the art itself:

This calculated attention to the precision of the installation against the imprecision of the work—an acknowledgement of the impossibility of control over a world of “weak” images or of strong images made weak, or of the ability to even make a strong image or to believe in them—so why not control what you can, their placement.

In Meacham’s press release for his Oliver Kamm show in 2007, which you wrote, there is talk about imprecision, “imperceptible flaws” and a reliance on Mondrian’s abandonment of the modular grid as “the tragedy of a rigidly ordered vision.” But here in the Beauchene show Meacham’s work looks incredibly ordered and precise next to yours. His appropriation of painting-as-object painter Frank Stella’s early minimalist stripe paintings (produced digitally on canvas here?) seems to emphasis this, until I notice a discrepancy in the two identical “Stella” paintings sandwiched together, both resting on the floor and leaning against a wall, one directly in front of the other. They are stretched unevenly making them out-of-square, their perfection undermined. On another wall I try to reconcile the high-low contradictions of a wannabe modernist Stella-esque painting of red Scottish-plaid fabric, stretched so the plaid’s axis is off from the stretcher bar’s rectangle, then placed on the floor leaning, like a drunken imposter, against another Stella appropriation. But which in the end is the impostor?

I read your press release for the Devoning Projects Chicago show that you and Meacham are also currently in, and liked your use of the Groys article, “The Weak Universalism”. You and Meacham, in both shows, address the same subject, Groy’s “weak image,” through opposite sensibilities at considerable risk: Meacham’s, cool and intellectually distant aesthetic, mining art history, distrusting it, showing us the holes. Yours, a sensibility that is down and dirty, an actual product or consequence of what you write: “the frantic pace of innovation in digital and communication technologies compresses our sense of time; rather than contemplated, our images are instantly ripped, posted and linked.” At first glance, your sensibilities seem so unrelated as to make no sense. Which is just the thing that requires me to take a closer look.

Here again, I’ve read something just before the time I saw your show that echoes the zeitgeist that our new friendship, our work and ideas, seem to be about defining. This time by Hito Steyerl, “In Free Fall: A Thought Experiment on Vertical Perspective.

It’s uncanny how your show at Nicelle Beauchene visually addresses some of what Steyerl talks about in her musings on the cultural (socio-geo-political) shift from the fallacious belief in our ‘stable’ location on the horizon (linear perspective’s influence on western culture since the Renaissance), to the new and equally fallacious ‘security’ resulting from our modern reliance on vertical perspective (aerial photography, satellite surveillance, google earth, GPS). Her idea of the “politics of verticality’, its hierarchy and the consequential state of “free-fall,” goes hand and glove I think with Groys’ “Weak Universalism”. And with your show:

Your paintings are literal documents of the ‘free-fall’—colors turning on axes (horizons?)—green below, yellow sun in the eyes, blue above, no below, white light, green ground, blue ocean, yellow, red, white…blackout. Paintings with multiple horizons like shards that cut corners. Paintings fast and windblown, agitated and desperate, futile and true. If ejected out of the last manned high-altitude bomber these paintings are the falling pilot’s ‘weak’ (insane?) analogue attempts at locating herself on the horizon for a safe landing on this side of enemy lines, as if the very act of painting on canvas was confused with using the screen on one’s console or handheld PDA.

Meacham’s appropriation of Stella is poignant as it rips that work from its formal modernist canon context, allowing it to become simultaneously more and less. Indeed, Stella’s work is the beauty and promise of a modernist flat verticality, horizon’s new perpendicular—stylized landscape of ridges and furrows viewed from a distance. Yet they also become cold and sinister aerial targets in violent video games, or do I mean real-life aerial-digital-targeting imagery in drone warfare? (Stella’s original inspiration having been Jasper Johns’ target paintings!)

***

Enter Bette Midler singing her ear-worm of a hit “From A Distance”. A film projected behind her of a body hurtling out of control, in free-fall through the atmosphere toward the ground:

From a distance the world looks blue and green,

and the snow-capped mountains white.

From a distance the ocean meets the stream,

and the eagle takes to flight.

From a distance, there is harmony,

and it echoes through the land.

It’s the voice of hope, it’s the voice of peace,

it’s the voice of every man.

From a distance we all have enough,

and no one is in need.

And there are no guns, no bombs, and no disease,

no hungry mouths to feed.

From a distance we are instruments

marching in a common band.

Playing songs of hope, playing songs of peace.

They’re the songs of every man.

God is watching us. God is watching us.

God is watching us from a distance.

From a distance you look like my friend,

even though we are at war.

From a distance I just cannot comprehend

what all this fighting is for.

etc…

But “Eyes Wide Shut” shows me that I can’t maintain that distant view because it’s foundation is false, unstable, and opague. “Eyes Wide Shut” shows me that while “from a distance” everything looks harmonious, I don’t really SEE YOU at all. From a far-away aerial distance, from the far-away distance of my comfy room with my joystick controlling my killer drone, I don’t hear your prayers or see what color rug you are kneeling on. I don’t see, “from a distance,” the ways in which you are like me, and the reasons why you are not. Because I am falling from high up, with eyes wide shut.

Written by Bradley Wester at 2:32 pm

December 16, 2010

BERLIN: The In-Between Place of Contemporary Art

Read my recently published article on Berlin in Pulse-Berlin. (Click below) After living there for the summer, this article compares Berlin to New York of the late 70’s and early 80’s and talks about the state of contemporary art:

My Summer in Berlin

The In-Between Place of Contemporary Art and Politics from a New York Artist’s Point of View

by Bradley Wester

Pulse is an open community interested in creative interdisciplinary and intercultural communication.The journal is created twice a year in Berlin, Germany, printed cumulatively every three issues, and gifted to bookshops, museums, reading rooms, and other exciting places internationally. Because Pulse is also an art object, with original illustrations and artwork, the print run is always a limited edition. Half of the printed version is numbered and given to contributors and collaborators. Many of the articles and interviews in Pulse Berlin are available in both English and German online. Everything about Pulse is given freely: each issue is created by a flexible and freelance group of writers, translators and editors who work in various cities around the world. Other articles and issues HERE.

Written by Bradley Wester at 4:44 pm